Blog 74 by Tan: Adventures With Opera Jack – Part 2

The next morning we rode the short distance to the BaAka settlement and met Jenga, the village chief once more. As Jack had informed us the BaAka are considered by anthropologists to be one of the most egalitarian societies ever studied and considerably more so than our own western cultures. Sharing, cooperation, and autonomy are front and centre of BaAka core values.

More signs of malnutrition in these kids. Sad.

Quite a different look to the nearby Bantu village.

The dwellings were more rudimentary and easily assembled and disassembled when it came time to move on.

Having a designated chief is a relatively recent development and one thrust on them by the outside Bantu tribes. Formerly decisions were reached by consensus and there wasn’t an individual leader as such. However as the Bantu tribes came to dominate the BaAka group, Bantu traditions of having a single authority figure to serve as the point of contact have became the norm. Jenga, as chief, was the only member of the tribe with closed in shoes and corrugated iron on his hut. It was he who dealt with the neighbouring chief, but by no means was he on equal footing.

The BaAka camp was starkly different from the Bantu camp. The most obvious difference could be seen in the look of the children, who here showed greater signs of ill health I am sad to say.

Jack handing over the gifts he bought for the village who’d be putting him up for the next two months or so.

Mick and I also handed over some bits and bobs we carry as gifts like razor blades, needle and thread (always a big crowd pleaser) and lighters or matches.

Local Bantu bloke helping himself to the BaAka gifted cigarettes.

The first thing we did when we arrived was to present the gifts Jack had bought for everyone. Mick and I also handed over a few things to the Jenga. These would later be shared out between everyone. One of the ways the BaAka maintain their egalitarianism is through the practice demand sharing. This basically means that whatever someone has will be given up if requested by others. The idea of one person owning a fork to the exclusion of others even when it is not in use is something rather foreign to these guys. Whilst it does a lot to maintain the egalitarian nature of their society it is one of the reasons that the BaAka haven’t taken up farming with great enthusiasm. Demand sharing serves as a disincentive to invest the time and effort in crop cultivation when, come harvest time, everything is given away when relatives, friends and neighbours some calling.

The BaAka recognised the necklace given to Jack by some Aka from Central African Republic.

During all of this gift giving there was a young Bantu guy with us. He was there with us ostensibly to help translate as he spoke French and the BaAka language. But it seemed a lot more like he was there spying on what the BaAka were being given by Jack….stuff that they could later bully from them. We were really suss on the guy and took an instant dislike to him. Perhaps we were wrong but we picked up on unspoken tension between him and the BaAka and also noticed him skulking on his own around the BaAka village looking like he was up to no good.

After the gift giving we all went on a tour of Jack’s new home. We were taken on a walk to where he would be getting his water and where he would be doing his bathing. It sure was going to be an experience for him.

On a tour of the village. Here you get a sense of the small stature of the Forest People.

A bit of a walk to get to the water hole.

And there it is. Where Jack would be sourcing his drinking water. We were glad he had a filter with him.

These guys were really keen on a photo of them drinking water. They got me to take a couple.

We also met some more members of the village. These villagers recognised Jack’s Aka necklace from the Central African Republic and Jack explained it was a gift from when he met Louis Sarno. The BaAka, who refer to Louis as “Lu-yay” were overjoyed at the mention of his name. They recalled Louis from the visit to the village 5 years earlier. It was impossible to forget a big white guy speaking their language. Jack’s association with Louis made him all the more welcome and one older woman in particular immediately took to Jack. We soon referred to her as Jack’s BaAka mum and with him placed snuggly under her wing we knew he was going to be A-OK here.

Here we are on our way to the bathing spot.

At the dark shallow pool where Jack was told he could bathe.

These guys know the forest.

On his necklace was two pink plastic turtles.

While hanging around the village we were introduced to some of the hunting tools of the trade. The snares were pretty interesting but the big-ticket item was the hunting nets. The nets are all hand-woven and forest derived, 15-20m long and about a meter high. We were jealous to know that Jack would no doubt go net hunting with everyone over the coming weeks.

Jenga with one of their snares.

Me with one of the snares.

Showing us how it works.

The animal most commonly captured on these net hunts are duikers, which are small (and cute) deer like animals. The blue duiker is among the most commonly hunted animal for bushmeat in the Congo basin. Interestingly back in 1925, a market for duiker skins developed in France where they were used to make coats and chamois leather. The market peaked in the 1950s when 27,000 duiker skins per year were being exported from forest areas of Central Africa. The greater demand for meat during the forced labor period of the time combined with this boom in the European market for the skins prompted the Aka to adopt net hunting over spear hunting, which was until that time the primary hunting technique.

These guys really opened up at the mention of Louis. Jack was in.

Jack meeting his BaAka mum.

The net.

Jack’s BaAka mum loving everything he does.

Love the look on this guys face.

This orientation towards net hunting greatly altered the prevailing social order. The sharing of meat became less egalitarian and the influence of the nganga (the traditional healer who directs hunting rituals on the net hunt) increased. In a net hunt duiker meat is not divided among all members, but those that were in part responsible for the kill, such as the person who spooked the duiker into the path of someone who wrestled it to the ground and to the person who ultimately stabbed it. Elephant or hog meat on the othe rhand are typically spread among the village.

Chaos theory claims the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can cause a hurricane on the other side of the world. In this case, a post-war fashion craze on the opposite side of the globe resulted in profound social change of a remote tribal group in the depths of the Congo forest. Whodda thunk it!

Some little kiddies.

This guy was such a handsome little kid. The sharp eyed may be able to make out his forehead tattoos

A motorbike toy fashioned from a thong (that’s a flipflop to any North Americans).

In a classic example of the danger of good intentions, foreign environmental groups, in their drive to protect wildlife and endangered species in the Congo have create a bad situation for the BaAka. In doing so have they have also worked against their own cause.

Some of the young men. The guy on the right is the one that makes trouble for himself later in the piece.

Here Jack’s BaAka mum is teaching him the BaAka words for parts of the body.

Due to Jack’s opera training he had a great proficiency for picking up foreign words and a great ear.

Learning the word for face. Love this photo.

Showing Jack how to light a fire.

Following instructions.

The little kid in the back of this photo had found a bit of plastic and was imitating me using the camera.

These kids enjoying the show…..possibly amused that a grown man was learning to light a fire – something they had mastered by 4 years old.

BaAka kids learn life skills very early on.

In many areas of the Congo forest the goal of protecting wildlife and natural habitats has led to Baaka being moved off their traditional lands as their millennia-old hunting practices are seen to conflict with conservation. But the fact is that no one knows the forest as well as the BaAka do and no one has a higher vested interest to protect it. Conservation is fostered through laws handed down from their ancestors. They have strict laws pertaining to sites and periods of hunting. For example, during the dry season, hunting stops as that is the period when animals give birth. And people are not permitted to set traps near waterholes where the animals go to drink. It is also strictly forbidden in BaAka to kill gorilla.

The kids had slowly become fascinated by the camera.

The boy on the right was a really happy little guy. The poor kid on the left had a massive swollen belly.

This gorgeous kid did lots of work around the camp.

Here she is looking after the new baby.

They were all extremely proud of the new baby.

As few as 1 in 2 BaAka children make it to 5 years old. This baby looked strong and healthy and loved. We hoped she’d beat the odds.

Meal prep.

The kids slowly got over their shyness with us outsiders.

The horrible irony of all of this is that in a number of places BaAka have been kicked off land for conservation reasons and that same land has been instead passed on to Bantu tribes who have no such connections to and dependence on nor qualms about shooting whatever might turn a profit. Often they pay displaced BaAka to shoot animals for them, providing them with a rifle, paying them a dollar for five day’s work or alternatively in booze. And you can guess how well all that works out.

Would you look at these bludgers!

Jack!

There seemed to be a some kind of schedule of access to the shade structure. This time was the blokes time.

Everyone was taking it easy.

These two looked like brothers.

Here you can see the BaAka tradition of teeth filing. It is an obviously painful procedure that BaAka usually get done between 10 and 15 years of age. It is really down to the individual if they want it. We saw both boys and girls with filed teeth and both boys and girls without.

The practice is usually carried out with a thick stick to bite down on, hammer, chisel and plantain paste to sooth the broken teeth.

Add to this the rise of large-scale logging operations in the Congo Basin and you find many BaAka caught between two worlds, neither of which cared to stake out a place for them in it. Forest life is getting harder for many BaAka groups. The increased access to their areas and the rise of the bushmeat trade has severely depleted forest once rich in wildlife. Hunting (and therefore eating) is less assured, making traditional BaAka life untenable for many. Others still have simply developed a preference for more modern comforts.

The adults also wanted in on seeing their image on the display.

Jenga’s wife and the mother of the new baby. This woman was incredibly hard working and we never saw her stop.

A boy with some seriously filed teeth.

Kung fu movies are incredibly popular in Africa. Somewhere along the line these guys had manged to see one…or hear about it from someone who had.

The encroaching modern world pushes them further to the brink through displacement by large-scale logging or national park establishment, forced settlement, not to mention the need to flee the violence of militia that occurs from time to time, especially in CAR and DRC. In the face of this some BaAka venture deeper into the forest trying to outrun the future, others see its already arrived and leave the forest in search of jobs. Such jobs might include working for logging companies, destroying the very forests they once called home. It is a sad state of affairs.

Part 3 to follow….

Blog 74 by Tan: Adventures With Opera Jack – Part 1

So there we were in Ouesso in the far northwest of Republic of Congo. We had no plans to stay. We were only there to get enough fuel and oil to see us across the border into Cameroon that same day. We were focused. We were determined. And then we were totally spun out to see a young white guy in a cap, walking down the street.

Smooth tar for the efficient extraction of natural resources. Wow. Cynicism from the first photo.

It really isn’t the part of the world you expect to see tourists so we couldn’t help but wonder what on Earth this guy was doing here. We figured he had to be either an NGO worker or a missionary. However before we got a chance to stop and ask, the fella was gone. It seemed a mystery that would remain unsolved. We got to the service station, filled up, bought a snack and were about to jump on the bikes when mystery young foreign bloke walks through the door.

Not far from Ouesso, our fuel stop before the border.

“We know what we are doing here, what on Earth are you doing here?”

We found out his name was Jack, from Georgia, US of A and he was in this far-flung corner of Republic of Congo for a rather awesome reason. We learned Jack was a trained opera singer on an illustrious fellowship that had him travelling the world experiencing different forms of traditional signing. He’d just spent time in the Torres Straight Islands in the north of Australia and planned to venture to Sweden to learn about the once outlawed form of singing called yoking. Afterward he would travel to the Tuva Republic to study their traditional throat singing. Jack was in Ouesso in order to gain access to Congo’s Forest People known more commonly as Pygmies (however by all accounts they don’t like to be referred to as this). The forest people are famed(amongst those in the know) for their unique singing. The Egyptians more than 2 millennia ago wrote about the Forest People of Central Africa who they held in high esteem for their singing and dancing abilities. Figuring the Egyptians were on to something, Jack had gone to much time and effort to seek some out.

Fast friends.

We gave Jack his first proper coffee in a long while.

Jack became a big fan of Aussie coffee culture during his recent stay Down Under. But the poor fella was so deprived of proper coffee of late he didn’t seem to notice the coffee grounds had gone bitter with age.

Despite our desire to cross into Cameroon that day we couldn’t resist the temptation of a good chinwag with an interesting person, so we all decided to go to lunch. Then all of a sudden it was 4:30pm and we were checking into the same guesthouse that Jack was staying at.

That night Jack told us of his present challenges in getting into the forest and finding a group to host and sing for him. Jack’s hurdles to this enterprise were manifold. Not only did he have to get himself to a village on no maps and somehow compel the members of said village to put him up for a couple of months, communicating though no common language; he also had to find a village with intact singing traditions, willing to sing for him. He had been in Ouesso for some time trying to get some direction on where to go and how to get there. He had a few leads but they didn’t seem to be going anywhere in the short term. And of the quotes he had gotten to try to get out to a village that may or may not welcome him was looking very expensive. He was unsure of what he should do. But he did have a name of a village that might fit the bill.

Even nomads have chores.

While Jack was sharing his difficulties in accessing villages to us, Mick and I gave each other a look that communicated very clearly the agreement that we should abandon all plans and help this guy out if we could. We told Jack that if any other vehicle could get to this place then so could our bikes. We told him that if he was up for it, we’d put him on the back of a bike and get him to where he needed going.

Bangui Motaba was the name of the settlement that Jack had been advised may suit his goals. This information was passed onto him by one of the foremost experts on the BaAka people (as the Forest people in this area are known). Louis Sarno is an American who one day heard a recording of BaAka singing and went on to track them down in Central African Republic and ended up living amongst them for more than 30 years. Louis was a committed devotee of BaAka singing traditions and his prolific recordings have made him a famed ethnomusicologist despite his lack of formal training. Sadly Louis Sarno passed away in April 2017.

General store in Ouesso.

An interesting take on the traffic cone.

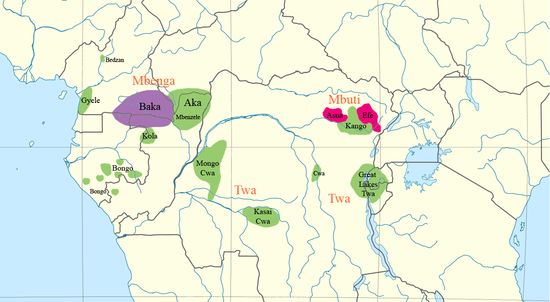

Forest People are found across Central Africa, through both Congos, the Central African Republic, Rwanda and Uganda. However it is the Forest People of Congo (the BaAka group) that have been most able to preserve their identity and traditions. This is largely the result of the lack of infrastructure and development. Poor quality roads are such an obstacle to movement that they have kept at bay the ills of the modern world, but also its benefits. Education and health services are wanting at best or more commonly non-existent.

But the pristine highway that bought us north to Ouesso has gone and changed things. Large-scale logging has arrived. And it was those logging roads that would get us to the settlement Jack sought. Bangui Motaba was only accessible by river until just a few years ago. It was with no small sense of sad irony that we would be able to visit the BaAka to hear their singing by way of the very roads hastening its demise.

The BaAka have had a hard go of things for quite some time. Such is the fate of many traditional semi nomadic groups they are easily dominated by outsiders. The Koi (ie. Kalahari bushman i.e. the fellas with the clicking language in “the Gods must be Crazy” franchise) are another example of this. They are also close relations. Small in stature, traditionally nomadic they are often pushed off their own land and denied their own resources. BaAka traditions have long been under threat but perhaps no more so than with the rise of logging. Logging has opened up access to their areas exposing it to increased hunting, migration, displacement, ready access to alcohol and just the general slow loss of tradition.

At our humble guesthouse.

Mick is still attempting to get rid of metal shards from the oil.

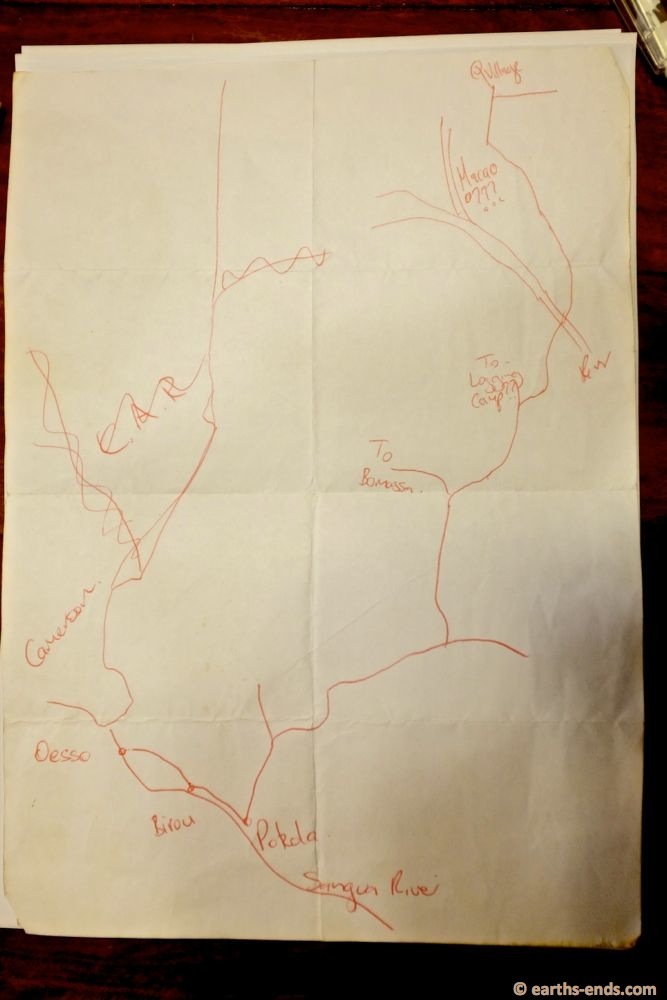

We had agreed to take Jack to a BaAka settlement, now we had to figure out where this place was. With the name of a village to work from and some second-hand verbal descriptions, we set about putting together a rough route map. With no maps to speak of, Michael and Jack headed for the local internet café. It was rough and ready and painfully slow, but the hope was it would be able to crank up Google Earth so they could try to pinpoint the village.

Repairing the collapsed oil filter so we had a back up to the new paper filter.

A dodgy spare is better than no spare.

Jack had a rough description of the place from Louis Sarno from when he visited some 5 years before. Jack was told the village was located at a bend in a river and he had a rough and possibly not reliable distance to get there by road from another source. Mick and Jack got on Google Earth and identified all settlements located on the bend of a river and then guessed the most likely spot based on the assumed distance. It was tricky as only some of the logging roads were visible, they had to just guess and thumb-suck the rest. Foremost in our mind was that whatever we did, we didn’t want to accidently cross over into the nearby Central African Republic. The security situation there was dodgier than a week old curry and we wanted no part of it. On this side of the boarder we would be sure to remain.

Now all of this internet-ing took two nights of attempts as the internet strength was low and it struggled with Google Earth. Mick would zoom and wait for the internet to catch up and then zoom in closer again then repeat. The first night he finally got zoomed in enough to get some relevant information when the guy on the next computer knocked the power board overloaded with extension cords and plugs and it knocked out all the power. Mick couldn’t face going through the tedious process again so put it off until the following night. The next night they got the job done.

The distribution of the different pygmy groups in Central Africa. It should be noted however that it is only the Baka, Aka and Mbuti groups who exhibit the unique polyphonic form of singing that Jack was seeking out.

With a map sorted, it was now a matter of securing supplies and gifts for the trip. Jack had been advised of useful gifts to bring for his prospective hosts. These included machetes (especially those with the flat end that makes them useful to digging), cigarettes, sugar, salt, cooking oil and clothing. Mick joined Jack on his shopping adventures as he had been given strict instruction by me, “for the love of all that is good and holy,” to buy a new shirt. Mick’s principal riding shirt ‘Big Red’ had deteriorated to such an extent it stank just to look at it.

Mick’s mud map. It would then be supplemented by us asking “Bangui Motaba?” whilst shrugging shoulders with much exaggeration to anyone we came across.

Jack stocked up on clothing of all sizes, bought himself a bucket for washing and at our insistence a couple of malaria test kits and treatments. We told Jack of our friend Pat’s recent experiences with malaria and stressed the point that if he tests positive for malaria he needs to get to a logging road and on a logging truck back to town as soon as possible. The treatment for malaria relies on a strict timing schedule for the pills that is very hard to manage while rocking 40 degree malaria fevers and the BaAka wouldn’t be able to help him with that. Jack promised us he would and we stepped out of worried parent mode and got excited for the ride ahead.

After advising Jack to look out for malaria symptoms we thought we better practice what we preached and do a malaria test on me. I had been feeling lethargic for several days now but this day it struck me as an abnormal level of fatigue. I felt utterly drained and at one point it felt a physical effort lifting my arms up.

The results of the test came back negative for malaria, which we knew to take with a grain of salt as results can be unreliable when taking malaria prophylactics. However I was pretty sure it was something else going on with me. I suspected some kind of parasite was at play. We’d been carrying a de-worming treatment for such an eventuality so I went ahead and started it. After what felt like a couple hours worth of some sort of major conflict going on in my guts, I felt utterly fantastic. So much so I can only conclude I had gotten rid of some stomach parasite that had be riding along with me for some time. I therefore highly recommend carrying a de-worming treatment for long-term Africa travel.

It was during all of these preparations that we all thought we might as well try and see some gorillas while we (and they) were in the general neighbourhood. Jack suggested we could drop in to the Department of Wildlife office in Ouesso and see if we could swing a good last minute deal, we readily agreed.

The remoteness and sketchiness of the location means Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park only receives a very modest amount of determined tourists…determined and cashed up I should say. Not like us. We were hoping by being on the ground and with access to our own transport for part of the trip we would be able to get an affordable visit. In the end we got them down to $US660 per person by skipping the $400 boat ride up the river and instead taking the bikes until the access to the park. Between the three of us we managed to convince ourselves to ignore the exorbitant expense of the trip and just go for it. We agreed to leave the next day.

We were excited for the gorilla trip but a bit anxious about the money we were laying down. We were finalising our packing the following morning when the parks people called us and cancelled the trip with no real explanation. We figured they probably couldn’t be bothered catering to busted-arse travellers like ourselves. It was disappointing, but budget-wise it was somewhat of a relief at the prospect of dropping over $US1200 had us sweating like the proverbial gypsy with a mortgage. But now writing this whilst gainfully employed once more, I am filled with regret that we didn’t go back and throw more money at the problem.

Nenaphur “Lilypad” became our local. Much shooting the breeze happened at that spot over the coming days.

The piggies stripped and being loaded into the ‘budget’ option dugout canoe.

The next morning we got ready to drop our new friend with a bunch of strangers in perhaps one of Africa’s last nearly untouched wildness areas. We had breakfast and left a bunch of our gear at the hotel for safekeeping so we could fit Jack and his gear on the bikes. We felt a bit uncomfortable to be fully decked out in safety gear when all we could off Jack was a spare pair of gloves. Even though it is very much the norm to ride bike gearless around these parts we still resolved to take it very easy along the route. We didn’t want to break him.

We headed to the river port to arrange for our river crossing. It didn’t take long for a copper of some description to spot us and tell us that we needed to go and lodge our planned movements with them. Jack had already crossed the river before so managed to avoid a second round of bureaucracy. We did the long walk to the police station in all our gear in the stifling heat so weren’t in a great mood when a number of police started to lay the familiar groundwork for requesting/demanding money.

We were really getting worn out by this kind of thing. Republic of Congo had been bad for it, not so much the requests for bribes but the way they went about it. We’d been in Africa over a year by now so were familiar with this kind of thing. However Rep. Congo was the first place where the requests had been menacing, aggressive and very mafia-esque. We were fed-up by the unrelenting nature of it. Like other times we were left just having to sit there and put up with copper after copper having a run at us for payment. In this case it was a non-existent payment for crossing the river.

Not too tough getting them in. Note the barge in the background we had hoped to take.

We stood our ground and gritted our teeth until they nearly cracked. When they saw we wouldn’t be paying to cross the river one of them came up with the idea that our documents needed to photocopied and we’d need to pay someone to go into town and photocopy them. They seemed pleased they’d found their in, but then we went and burst the collective bubble by provided them with our own photocopies. Eventually someone senior came along and said we could go but there were a few police that were really shitty at us as we left. It hardly puts you in a good frame of mind.

We got to the port and started trying to get across the river. There were two options; by canoe or by the barge that took vehicles and logging trucks across. Officially the barge is supposed to allow bikes on for nothing. But not in our case, obviously. The barge guy was licking his lips and quoted us a ridiculous price. The canoe option was a lot more hassle and it would require us paying helpers to get in and out. And while the canoe looked sturdy enough there is always a certain element of nervousness that comes (at least for me) with crossing a big river with the bikes precariously balanced in a dugout. Both the price of the canoe and the barge option were going to be an outlandish 25,000CFA (USD45).

Unlike past dugout rides with the bikes this huge one seemed safe as houses…sort of.

It is a little hard to describe how Mick and I were feeling at that stage. Semi-muted rage might come close to the mark. We were just soooooo over this sort of Congo stuff. The feeling of being set upon everywhere we went combined with big man tactics of police and those of that ilk; having to constantly stifle our frustration in the face of explicit and implicit demands. After weeks of being on edge with guards firmly up we were starting to lose control, starting to get way to worked up to achieve decent resolutions and our decorum was starting to fly out the window at an impressive rate of knots. Jack did well to put up both with us and the hard bargaining bargeman.

Getting the bikes out of the dugout proved trickier.

In the end we went with the canoe option. I just couldn’t bring myself to giving money to the bargeman. The nasty, arrogance sprawled across his face just got me disproportionately angry, it was the same look we had seen on the mugs of anyone with any level of power over others in Congo. I wanted nothing more than to wipe it off for him. I acted like a petulant jerk. It wasn’t such a big deal for us as we did have money and could leave the place. Not so for others, and I was angry for them as well as myself. The difficulty and injustice of the place was wearing us down.

Fortunately we had this bloke’s help who was happy for the payday.

So after spending a lot of futile time arguing with them about the price knowing that we were getting completely shafted we simply had to relent. Jack did really well at dealing with it even though he was obviously annoyed by the openness with which they were ripping us off.

In the end the canoe guy was allowed to load us from the shore and we basically did all the manual labour to get the bike in ourselves. We got the bikes in without too much difficulty but getting them off on the other side of the river was another matter. In the end we paid USD6 for a couple more pair of hands.

We didn’t know it then, but we were in a different world on this side of the Sangha River.

Once the bikes were repacked we were off and rolling. It was to be slow going with Jack on the back and we kept our speed at no more that 60km/h. It was interesting riding and our laid-back pace gave us plenty of time to take in the surrounds which were night and day to the Ouesso side of the river. As soon as we were moving we found ourselves passing people of such diminutive size that we knew they were members of the BaAka group. Apart from one World Wildlife Fund vehicle the road belonged to us…..and the dishearteningly steady stream of logging trucks.

It didn’t take long to encounter logging activity.

One of the many.

After not too much time we hit a small township of Pokola where we bought some deep fried dough balls and confirmed we were heading in the right direction.

This pristine, primary forest had be opened up like a banana.

We only progressed another 80kms down the road before we made it to the outskirts of a timber camp called Ndoki 2. There was a security gate, which I think was manned by people from the department of forestry. The fellas there were nice and helpful and said we could camp next to their offices. It was a pleasant change from how we were generally treated by men in uniform. It was getting late in the day so we took them up on the offer.

Mick had been taking it easy with Jack riding pillion and had seen this sinkhole ahead of time.

We set up camp around the corner of the office in front of the MTN cell phone tower. The security guards of the phone tower were similarly kind and offered us the use of their kitchen area and a place to sit. We made a dinner of noodles and then set about going to bed. But before we did so it was time for Jack get singing. Jack had agreed that as payment for taking him into the forest he would need to sing to us each night of the trip. So Jack paid his day’s debt and impressed us all by belting out a French opera number. After Jack had finished the cell phone security guy started singing what appeared to be bible verses in French. After retiring to our tent we were serenaded to sleep by the sound of singing combined with the dull hum of the tower and a forest full of insects. We couldn’t help but smile to ourselves at how unexpected a day in Africa can be.

Jack got out to inspect it and asked Michael what would have happened it they had hit it. Mick’s reply – “Nothing good.”

The fellas getting nice and acquainted.

Jack was an incredible sport. Our bikes down have pillion foot pegs. In Australia it is cheaper to register a bike as a single-seater so we remove the pillion pegs.

The next morning we packed up and said our goodbyes to the cell phone tower guys and hit the road. We were hoping to find somewhere to get a bite to eat in the nearby logging camp but found it deserted. After downing a couple of biscuits we continued on until coming to yet another logging camp. This one was of considerable size with some impressive looking accommodations that could only have been for foreign management level staff. All the logging operations we passed up until this point appeared to be French or Belgian owned.

“Sorry Jack – I need to get a photo of you like that for you mum.”

At this camp we were able to confirm we were heading in the right direction for Bangui Motaba and get some dough balls for breakfast/lunch. We were also able to stock up on some more food. Jack planned to take some general supplies for his time with the BaAka but apart from that it was his intention to eat as they did. We were worried for the guy and I found myself going into full Italian Nonna mode and wanting to load him up with food to take. Knowing he would be there over Christmas we got Jack a small gift of a couple of single serve Nescafe sachets and a tiny packet of hazelnut spread. We figured after a month of a forest diet it would be as good as getting an X-box come Christmas.

Our digs for the night. Lots of infrastructure points like this have 24hr guards that live on the site. For what period of time and pay I do not know.

With more riding came more logging trucks and disturbing scenes of pristine wilderness permanently interrupted. As we rode onward Michael and I had the chance to think about all it was that Jack was about to do and we were increasingly impressed, and to be honest, a little nervous for him. He was going to be over 300km and a river from a town, that itself seems a long way from anywhere. At that point we didn’t even know if this village would accept his presence, and if they did, we didn’t know if the village would be at all interested in singing for him. This could be a lot of effort for a potential non-starter. But it was to be his best bet…. and time would tell.

Jack had a gift for make friends.

Looking for some food…and coming up empty.

The best way to deal with the logging trucks…

…was to get well out of their way.

Towards the afternoon we arrived at Mbouli village, where Jack would need to negotiate access to the nearby BaAka camp with the Bantu village chief. The fate of the Forest People was such that they were in a feudal-style, semi-ownership status with the Bantu tribes. The BaAka (along with the Koi) are among the first people in this part of Africa. Bantu groups actually originated in the north of the continent and have travelled south over time, overwhelming groups such as the BaAka in the process. Historically BaAka were slaves to members of the Bantu ethnic group. While out-and-out ownership is disappearing, Bantu attitudes of superiority towards the BaAka endure. The BaAka are perceived by many of the Bantu group as wild, hopeless, dirty and simple, and thus has followed a long history of exclusion and ill treatment. It’s the age-old clash of between farmers and hunter gathers at play, with the latter seldom, if ever, coming out on top.

There was no shortage of these trucks. The only bright side of their presence was that Jack would be able to get a ride with one if things went pear shaped in the village.

Me goofing off.

Upon arriving at the village Mick discovered that he was just one river bend off in his estimated location of Bangui Motoba. Not bad for some secondhand verbal details of a guessed location. After arriving there was a bit of waiting around until the village chief showed up and the negotiations began.

The tracks got narrower the closer we got to our destination.

The fellas in good spirits.

We were offered a cup of local booze while someone ran off to grab the head of the nearby BaAka camp. Mick and I sat back and left Jack to negotiate his access to the BaAka. It all felt pretty appalling to be doing so, as though the BaAka were the property of the Bantu village, but that was the way the mop flopped out here. Jack was well acquainted with the BaAka state of affairs. Luckily for Jack there was some semblance of a shared language as he had a decent amount of French to converse with through his opera training. There wasn’t a word of English spoken.

The negotiations begin.

Some BaAka from a neighbouring settlement.

Jenga, the chief of the BaAka that Jack would be staying with.

I don’t recall much of the details now but the initial price demanded for staying with the BaAka, (along with the gifts offered up to the chief) was an outlandish sum that was perhaps feasible to National Geographic photographers and well-funded anthropologists, but not a young, independent bloke like Jack. From very clouded memory they were after something along the lines of $US700, which they said would have given him several years worth of access. Jack explained that he was just a lone person not a rich, funded expert and that he didn’t have that kind of money. The negotiations continued. Once again we were impressed by Jack’s cool nature, patience and more than decent command of French.

Negotiations continued. Mick rummaging the French-English dictionary in order to keep up.

Getting settled for the evening.

Jack – one cool dude. After that ride and hours negotiating he was still in a good mood.

We were the evening’s entertainment for the village children.

Eventually a sum was agreed to that was nowhere the initial sum. Mick thinks in the end it might have been close to $100 that he ended up paying but we could be wrong. During the negotiations a number of BaAka from another community showed up and were dead keen to get the party started there and then. They knew most, if not all, foreign visitors to the BaAka were there to hear their singing. And they knew they could use that to get booze. Alcohol had become ever cheaper and easier to get since the explosion of logging. And in the face of a difficult and oppressive existence alcohol was proving popular source of temporary relief. And it was devastating communities and eroding traditions. We’d see hints of this during our short stay.

They were some cute kids.

The River.

Bath time.

It was at the insistence of the Bantu chief that we spent the night in their village before going on to the BaAka village that lied little more than 500m away. There would be no singing nor boozing that night.

We set up camp near the chief’s hut and swiftly became the source of much amusement to the village kids. We took advantage of a small window of privacy to have a wash in the river, which we later found out was home to a reasonable number of crocodiles.

We got just enough privacy to get washed before these guys showed up to gawk at us.

The only way to get to Bangui Matoba was to arrive by boat here.

Playing with the camera that night.

The village in the light of day.

Cut a pretty quaint picture.

The Chief’s lodgings.

Not a bad spot at all.

Shame about the crocs….but they paid us no mind.

Blog 73 by Tan: Seeing the Wood For the Trees

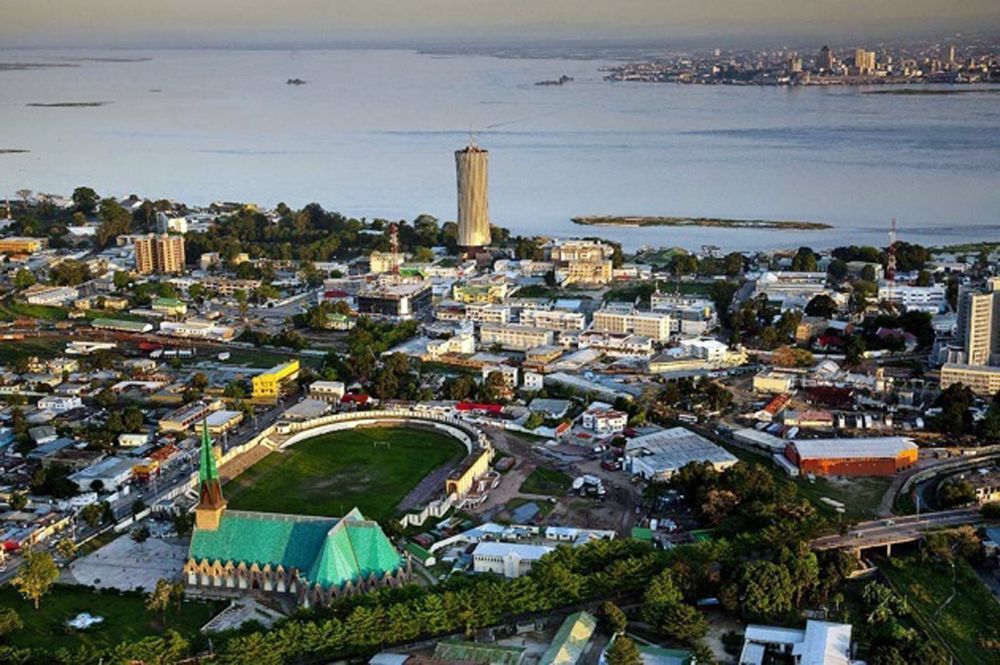

The Brazzaville side of the river was a breeze in comparison to the Kinshasa side. There were nowhere near the number of police, immigration and customs people around and things were a lot less hectic. One of Boris’s E.C Air employees was already on the Brazza side waiting to help us with our paperwork. After grabbing our passports and documents he disappeared for 20 minutes or so only to emerge with papers in hand and approval for us to move on. We were on our way.

Kinshasa and Brazzaville were like night and day. Brazza’a population at just over 5 million making it positively sleepy in comparison to Kin. While we loved the energy of Kin, the calm vibes of Brazzaville were a welcome change. We were exhausted, both physically and mentally. We had been getting by in Kinshasa by the enthusiasm of our bike club mates and by the need to get things done. Now with visas in order for the road ahead, the bikes running well and our friends in Kin gone, we crashed.

The rival cities of Brazzaville and Kinshasa facing off across the Congo River. One of my favourite authors on Africa Michaela wrong writes: “From Brazzaville to Kinshasa, from Kinshasa to Brazzaville, residents ping-pong irrepressibly from one to another … depending on which capital is judged more dangerous at any given moment.” Net pic.

Our plan was to stay just a couple of days in Brazzaville then get going. A little anxious about the amount of money we spent in Kinshasa we had planned to take advantage of the free camping offered to Overlanders at Hotel Hippocampe. It is not a proper campground, just a space on concrete behind the restaurant with access to showers that the owner generously offers free if you agree to eat in the hotel’s Chinese restaurant.

Sergio and Anders. Anders has a fantastic blog full of great stories and invaluable information for travellers.

However when we got there and the rain started to pour and the prospect of a night in a leaking tent got less attractive by the minute. Instead we wrangled a good deal on a room and took it. That night we slept for more than 14 hours. Our exhaustion was complete. We decided to stay another night….and each morning we decided to do the same again.

One day we finally decided to leave and brought all our bags downstairs only to bump into another Overlander, a Swedish guy named Anders travelling on an old Africa Twin. Anders had recently been reunited with his bike after 10 months of recuperation back in Sweden. He had suffered a broken leg and knee damage in an accident on a slippery mud track in Republic of Congo not far from the Gabon border. Ander’s, with a broken leg and little options, arranged to store his motorbike and belongings in a police compound for however long it took to fix his leg and return. A cynical person might have written off his chances of having anything to return to, but in this case they would have been wrong. The bike was exactly where he left it. Anders is a super interesting and well-traveled guy and before we knew it we’d spent just about the whole day chatting. We lugged all our bags back to the room and spent another night.

Duct tape for the win. Our tent has served us well however the seams had started leaking on us.

It was one false start after another before we realised we’d be best served not trying to force our departure and to just leave when we felt up to it. If it took 5 days or 2 weeks for that to happen, then so be it. We were utterly travel fatigued. And the only cure for that was a bit of down time.

While at Hippocampe we saw to more bike chores. The principal concern was all the metal strewn through the motor. Mick changed his oil and cleaned the filter again and fished out more aluminium. Ridding the motor of it was going to be a slow process.

Mick giving Anders some pointers.

Another oil change and shrapnel retrieved.

And more again.

That day we made the decision move somewhere more modest so we didn’t have to worry about blowing budgets. Just as we were making a plan to do so a super cool Brazilian bloke on a Super Tenere named Sergio spotted our bikes and pulled up to say hi. Like Anders, Sergio was one heck of an adventurer. He has been doing his round the world bike travels over a long period of time and region by region. On this particular trip he had travelled from Japan, through Russia and Europe and to Congo in 4 months. Meanwhile it takes us 4 days to check out of a room. He was going at a cracking pace. It was not our style but we were impressed. Sergio told us he was staying at a simple hotel on the other side of town that had space for the bikes and was only $US16 a night. We made the move.

This bloke showed up with this stunning old Tenere.

Our new budget lodgings.

A day later Anders and Sergio moved on and crossed by boat to Kinshasa together. We found out they didn’t find the crossing too stressful but it was an 8 hour process that set them back $US250 each compared to our relatively quick, $335 for both bikes crossing. Making us grateful once more for the help of the Kinshasa bikers.

After spending several more days taking it easy and hitting Brazzaville’s Lebanese restaurants and fantastic patisseries, we were well fed, well rested and ready to move. Unfortunately however, we had not planned on fuel shortage in the capital. We were told it was a reasonably frequent occurrence for this oil-producing nation. Lines at service stations were so long that cars were spilling into the streets blocking traffic all over town. The police had been called in to supervise the mayhem. One of the coppers must have felt sorry for us waiting in the sun in all the bike gear and waved us in, allowing us to skip the long queue, fuel up and hit the road.

La Mandarine became our second home. It is a Lebanese run French patisserie that knocked my socks off. It was hard to leave. Net pic.

The Basilique Sainte-Anne stands out in a city of few grand structures.

The slow start and roadworks on the way out of the town meant we covered just 150km for the day. It was our first day of riding in Republic of Congo so we had yet to familiarise ourselves with the lay of the land. What our 150km did show us was that the place was a lot less densely populated than we were used to. We were travelling north on a new, lesser-used highway. We were out in the sticks and could see little in the way of accommodation. Even camping didn’t look promising as we rode past mile after mile of tall grassland with deep concrete culverts separating us from subpar but do-in-a-pinch camping locations.

Long lines for fuel had us leaving town late….or should I say later that usual.

We reached a small village at sun down and tried to find a guesthouse. Soon it was dark and we were still searching for somewhere to lay our heads; a first for the trip. Our almost non-existent command of the French language wasn’t helping matters. Eventually a nice car pulled up nearby with a Chinese guy inside, no doubt working on the huge construction project we had passed earlier in the day. He spoke no English so we used Mandarin to communicate our need to find a place to sleep. He spoke French to his local driver who then spoke the local language to someone else. They confirmed there was no guesthouse in the village but found someone to take us to a local priest who might be able to help.

The church in the light of day.

The bikes sanctuary for the night.

We were led by car far off the main road, though a dozen small plots of land past tiny huts made of corrugated iron. Eventually we came upon a big building of corrugated iron. The young priest came out and said we could park the bikes in the church and spend the night in a spare room of the church housing block. It was such incredible luck we’d come upon this place. And if things couldn’t get any better, the room had power and the fan stayed on all night. The next morning we thanked the priest for putting us up and left him with a donation to the church.

Saying goodbye to the priest.

The translator and the Chinese road inspector. The Chinese bloke kindly informed us we were “so cool”.

After saying our goodbyes we headed back to the village to fuel up. While we were there another Chinese construction company vehicle showed up. A young Chinese guy spied our bikes and came out with his translator to say hello. So there we were, a Chinese, a Congolese and an Aussie chatting away in Mandarin in the middle of Congo. The translator told me how he had spent 7 years studying in China on a Chinese government scholarship. His Chinese was excellent. The Chinese guy was from Inner Mongolia and was on his first short trip to Africa and seemed to be stunned by the experience. He was there to inspect the road however construction work hadn’t started due to government delays. Both guys voiced their frustration at the government’s inefficiency and demands.

Plenty of scenes like this on the road north.

And plenty of empty road.

Not long afterward another car showed up with more Chinese speakers inside. These fellows were Malaysian Chinese and once more we got chatting. I asked them if they knew which towns might have accommodation on the way north. We were keen avoid another nighttime scramble for a bed. They gave us some recommendations and then told us that we should stay with them that night at their plantation. He gave us his phone number and told us to call him when we arrived in Marquoa and that he would give us directions to the plantation from there. It seemed too interesting an invite to pass up.

A typical roadside lunch. Central and West Africa is all about the Laughing Cow – a dull yellow goo that claimed some relationship to cheese.

No complaints about the fruit though.

Mick waiting while I hunt down a pineapple.

We had a simple ride up pristine tar with little in the way of towns along the route. As the day wore on we experienced a very rare sensation of getting rained upon. So far, in almost a year and a half of riding in Africa, we had been rained on less than a handful of times. With the storm clouds brewing we had to rack our brains to recall where we had stored our wet weather gear.

While we were searching through bags the heavens opened with a fierce though short-lived downpour. Unfortunately for Mick he discovered that his Jackson Racing WON-Z (which cost an arm and a leg) had a failed zipper. He’d only used it a handful of times so that was disappointing and inconvenient in that moment.

The colour.

Target acquired.

Buying baguettes lathered in nutella type spread.

Ready to roll.

It was poor timing with the wet season threatening us. And the product warranty did us little good in the middle of the Congo. It would have cost a small fortune (probably exceeding the value of the suit) to pay to courier the suit home and back to Africa and pay what would no doubt be ridiculous import taxes on the goods. A big part of the reason that Mick splurged on the suit was to minimise the chances of gear failure during the trip. “No chance of that happening if we purchase top of the line products, right?” This is a myth and we can’t quite believe we fell for it with a fair bit of the gear we purchased. And here we were carting a rain suit with a broken zip worth very near to the per capita GDP of Republic of Congo. You live you learn.

Not exactly waterproof.

After passing nothing but grassland and scarcely a single vehicle we came across a huge airport. We were confused who the airport serviced until we saw this huge 5 star hotel in the middle of nowhere. We knew it could only mean one thing. We had to be in the hometown of the President and this was his hotel. Apparently we were right.

Just outside of Marquoa we were met with an utterly bizarre sight. After hours of riding past nothing but grassland, swamp or forest, we came across a near to full-scale replica of the White House. After confirming that Michael could also see a giant copy of the White House we started to ponder why it was here. It didn’t take long to agree that it was most likely the ridiculous personal vanity project of one of the richest people in the country, who is no doubt a public servant. Sure enough when we asked about it someone told us it was the house of the Republic of Congo Treasurer ,who by the looks of things, might be dodgier than a week old curry. We didn’t want to get spotted taking photos of the place so just shock our heads and rode on.

We were set to arrive at the plantation on sundown however we weren’t counting on hitting a road block ….and being kept there. The Gendarme in charge was a proper jerk to us. Being at the end of the day and pitch black we just weren’t in the mood for this.

He went straight into the stern, rude Mr hardarse mode we had become so familiar with in Central Africa. We were less than a kilometre from the plantation, tired and hungry and without the energy or patience to deal with an aggressive shakedown. Perhaps he sensed that so went in hard.

More views on the empty road north.

After taking our international drivers permit he demanded our insurance. We didn’t want to take out all our documents so tried to blow him off, distract and ignore him so that he’d get tired of us and let us get on the bikes and go. This was generally a successful tactic but was not that night. We explained that we were tourists and going to visit our friends at the plantation and needed to go. We were to discover that admitting to any association with the company guaranteed a hearty extortion attempt. It was no coincidence they were set up so close to the plantation gates.

Approaching sundown and still 70km to go.

He came up of his office with a fine of 10,000CFA (US16.70) each for us not having insurance. We did have insurance (ok it was fraudulent but convincing insurance) but he said too bad I’ve written the fine you have to pay or I am not giving your licenses back. Both of us lost our temper pretty good and proper. And in what can only be described as a bad move, Mick took the fine, scrunched it up and threw in on the ground. Yep. We went feral. The Gendarme, rather predictably, did not like this.

Meanwhile our Malaysian friends showed up looking for us. I am guessing they had figured we were stuck at the roadblock having our pound of flesh extracted. Qian cooled off the situation and we paid the money as any further resistance would have been felt by the fellas at the plantation.

Early morning over the plantation.

The plantation slowly coming to life.

At the plantation Qian, the manager, already had dinner there waiting for us that he had cooked himself. All the foreign workers cooked for themselves as this was no cushy expat job for them. We chatted for a while and learned that the roadblock arrived soon after they did. Despite being residents of the Republic of Congo they are made to pay between $US5-10 for every non-Congolese in the vehicle that passes the checkpoint, no matter how far they intend to travel and no matter that it is a public road. The plantation had become a cash cow for these guys and they never missed and opportunity. We didn’t stay talking for too long as the guys get up at sunrise to start work. They showed us to our cabin for the night and we were soon in bed.

The surrounds.

The plantation camp.

We woke up before sunrise. Despite the comfort of our simple lodgings I slept poorly due to nightmares and being angry at the Gendarme from last night. Our time in Brazzaville was supposed to have relaxed and soothed us after some intense weeks. But there we were exercising the patience of a three year old when pressed. The copper was so intense and mafia-esque compared to what we had experienced thus far in Africa, even in DRC. They were fat cats used to getting their cream. And while that was unpleasant the more worrying matter was that we had both handled the confrontation poorly…like really poorly. We can’t be making a habit of such failures in judgment and control. We resolved to keep our shit together.

Some of the plantation gear.

The camp mess.

We went to the mess for breakfast and chatted away the morning with some of the Malaysian and Pilipino workers. These guys were mostly mechanics and heavy machinery operators. They told us about their lives there and we were struck once more by the hardworking and isolated existence of these guys. They work every day for 11 months then they get one month a year off which they spend back in their home countries. They cook for themselves, have cold showers for 11 months of the year, and have very unreliable internet access for keeping in touch with family. It is not all that surprising then that they were happy to have us at the camp as we represented a bit of a change from the norm.

The workshop.

Mick setting up shop.

Mick fashioning a makeshift gasket out of old exhaust tape to make his leaking exhaust a bit less obnoxious.

Mick informs me this t-shirt is perfectly fine.

The guys gave Mick the go ahead to use their workshop to try once more to rid the engine of excess aluminium in the oil. Mick’s bike had been running at about 128 degrees even at 90km/h which was about 30 degree off normal. This time Mick wanted to flush out the oil cooler with petrol and compressed air. It worked well and he managed to dislodge a good amount of aluminium. Once all back together the bike appeared to be running closer to its normal temperature range.

Time for another flushing.

Did you know Mick played the oil cooler in his high school band?

The compressor was effective.

Glitter!

The plantation fellas invited us to have lunch with them and suggested we stay another night so that we had time to do a tour of the plantation. We didn’t want to pass up seeing more of the place so happily agreed.

Lunch with one of the Pilipino guys and Mr Wong.

Mr Wong, one of the operators at the timber plantation, took us for a tour the next day. It was a huge operation but was completely empty. We toured both the palm oil plantation and timber yard without seeing a single person…let alone a single person working. It was a bizarre sight but very much the norm according to the foreign workers who said though the locals workers are paid for an 8 hour shift they generally only worked 2-3 hours per day. But today was payday. And they won’t work on payday.

The oil palm plantation.

Seeing my first ever oil palm up close. Mr Wong told us that there were many gorillas in the area. The gorillas come from the forest to eat the palm oil fruits from time to time. I asked what they did when the came down and he said they have to chase them away. “You can’t hurt them, it is forbidden and you will go to jail.” He also said they have seen elephants on the site as well.

The Malaysian guys were frustrated and said they couldn’t understand the local workers refusal to do their 8 hours shifts. They said how they were paid above the government mandated minimum wage and that there were no other jobs in this extremely poor area. These guys were of the mind the locals should be glad for work and income for themselves and their families. The complex attitude to work by Africans under foreign employ was out of their comprehension. The “work hard to get ahead” mentality hasn’t always held true throughout Africa’s history. They asked us somewhat rhetorically “can’t they see that they are destroying the project? Can’t they see that we will close down and there will be nothing for anyone here if they don’t work?”

Qian told us that the Indonesian and Malaysian plantations, an average plantation worker can transplant 120 palm plants a day. On this plantation the workers only do about 40. In the past they say they have tried to push the employees to do 50 transplants a day but they were met with such fierce opposition, often resulting in the workers walking off the job for days. Anyone who wanted to work or do more transplants that the others tended to get hassled or beaten up according to our potentially biased new friends. But this I suppose is not too dissimilar from unions of old in various parts of the world.

Palm oil fruit of the African palm oil tree. You wont go a day in you modern life without using or eating something derived from it. There are over 200 names for palm oil derived ingredients so no wonder we don’t know we are using it.

The food industry is responsible for 72% worldwide usage of palm oil. Personal care and cleaning products account for 18% of usage, with biofuel and feedstock taking up the last 10%.

Either way, at one third the expected productivity and in the face of incessant corruption and significant sovereign risk, it was obvious the economics of the project must be ‘all up the shit’ for lack of better phrasing. The project was far behind schedule and bleeding money.

Palm oil plantations are capital and labour intensive at the early stages. Apart from money from the selling of timber, no money comes through the door until palm oil trees reach maturity which takes between 4 and 7 years. Even then harvests are modest until they reach full maturity at about 15 years. To save money the modest contingent of foreign staff from the Philippines and Malaysia had recently been cut back by almost a dozen. I can’t recall how many foreign staff there were but it seemed less than 20.

Mick clearly not worrying about snakes.

Look closely and you might be able to see the palm oil trees beneath the weeds.

We weren’t surprised to hear they were under significant financial strain. Qian told us just this one plantation was $US40 million in the hole and things weren’t looking good. This presents a real chance of the company abandoning the operation, leaving the area potentially in a worse off situation, rendering all the destruction all for nothing. The company’s infrastructure, quite literally paving the way for even worse destruction at their departure from uncontrolled logging, hunting, wildlife trafficking, mining and land speculation from any and all and sundry.

A nursery.

More mature trees awaiting transplant.

The plantation was approaching the time for their first harvest and it seemed the fate of the entire project was hanging on it. Qian was worried about having enough staff to do the necessary work given the short working days. They seemed at a bit of a loss of how to deal with it all and acknowledged their workers had the upper hand. It was a similar story with the government officials, inspectors, police and gendarmes who would show up looking for cash. If the company wasn’t forthcoming they would threaten to issue fines, order workers to stop work for days or shut down operations. Apparently Christmas day at the plantation would see a procession of officials, government workers, the police and gendarme showed up for their Christmas gifts. The plantation mangers feel they have zero choice in the matter. Corruption is corrupting.

The old and the new.

Not all trees are created equal.

We first inspected the palm oil groves and were surprised to see how nearly completely overgrown they were. In some sections you could scarcely even see the trees for the weeds. My Wong was so disappointed at their state head shake and look at his feet anytime he looked at them.

The timber industry in the Republic of Congo is mainly geared towards the export of logs though the government is trying to encourage secondary processing to see greater economic benefits to the country. It has legislated that 85% of timber exported needs to be processed in country. Hence this timber mill.

I’ve read that this company has been pinged by inspectors for mislabeling logs for export. I’d guess they may have been re-using trunk IDs to get more than their 15% of logs exported and/or avoiding royalties.

We then moved on to the timber harvesting part of the operation. We saw first hand the sad and sobering consequence of the veracious consumption practices that has ensnared the cashed up parts of the planet. Intellectually I knew of such destruction, but that was sitting at home, not standing at ground zero in the Congo forest. And knowing isn’t seeing and feeling. We did both while standing at the junction of beautiful lush forest and the ugly palm groves that have replaced it. It is only the most heartless among us that could be without emotion to be in a place like this, touching the trunk of a tree as wide as you are tall, stamped and ready for export.

Some of the smaller logs.

In 2015, 57% of Congo’s timber and wood product exported to China. But at least a third of what China imports ultimately gets exported to the rest of the world.

Raw logs like these ones are the least economically beneficial way for developing countries to exploit their timber resources. They provide less royalties, employment and industrial development but greater profits to foreign timber companies and the manufactures they provide for.

I don’t know the stats for Congo but as an example a cubic meter of the valuable hardwood timber from West Papua yields only about $11 to local communities but around $240 when delivered as raw logs to wood-products manufacturers in China. And that’s before further value added through secondary processing.

After leaving the plantation we did some reading up on the project. The company is criticised and for its secrecy, their proximity to national parks, their use of offshore tax havens and shadowy ownership, where two of the major investors are not known. However it was mentioned to us that the project owners were a huge Malaysian company that owned shopping malls. Conservationists claim that the palm oil plantation is just a cover and that their intention was only ever to log forests and trade timber. This was certainly not the impression we got.

If a tree falls in the Congo forest, and no one hears it, did it still get turn into shitty, flat pack furniture?

This was a monster of a tree. Freshly felled it still looked so alive.

Not sure what this wood is destined for. Possibly high value timber flooring.

According to these guys they don’t do well at all off the sale of timber and actually often run at a loss. I’m inclined to believe them. Qian told us the transport is what wipes out all their profit margin. The port of Pointe Noire is located in the far southwest of the country. The main timber zones in Congo are in the south and the north. Timber from the south is generally transported by a combination of river and road to Pointe Noire, while timber from the north is generally transported to Douala in Cameroon. I don’t know why but these guys could not transport to Cameroon. They were left having to truck all the way from the north to Pointe Noire in the southwest route about 1100km away. They told us that each truck was forced to pay at least $US300 worth of bribes each leg of the trip. The timber side of the business seemed a troublesome disappointment as things stood. They were all about the palm oil.

It was a somber visit, like visiting a cemetery. Suffice as to say I will never approach the purchase of a wood item lightly again.

Mr Wong’s tool of the trade. He told us his is a very dangerous job. I’d believe it.

More remnants of big trees logged.

We were a little worried about peoples’ perceptions of our visit to the palm oil and timber plantation. The guys there were kind and generous to us outsiders and we hated the thought that people would read this blog and see their pictures and think ill of them.

Contemplating the world.

I’d acquired a loyal fan club amongst the plantation dogs.

My favourite of the lot. I named her Pikelet.

The tower was for getting phone signal.

The camp from on high.

Plantation views.

The fellas at the plantations aren’t villains and I would argue they bear less responsibly for devastation wrought than the average middle class family from anywhere in the developed world, burning through resources like it was going out of fashion; a new renovation here, an update of the perfectly functional furniture there an “oooh this laundry detergent is so much cheaper than the rest.” The main reason for the prolific use of palm oil is that it is the cheapest form of vegetable oil, which allows for the price cuts we so crave and the profit margins manufacturers and retailers demand. It is all a part of the high cost of a low price culture that stimulates consumption.

Getting sorted.

Breakfast and cat petting.

When we returned to the camp we saw the workers in high spirits and all lined up, waiting to get paid. Payments were made one-by-one and involved a great deal of arguing according to Qian. He said almost everyone argues about their overtime and holiday pay (even expecting it if they took all their holidays already). It is obviously an exhausting process through which Qian had become an expert peacemaker.

As the afternoon wore on things got noisier and the music got louder, the booze flowed and the salaries were spent. Later we heard enthusiastic partying and then rowdiness and fighting. We found out the next day that the cops came to break up some trouble…and to ask for money. It was a sad but not unfamiliar state of affairs that was repeated at the plantation every month.

Our host Qian who thought nothing of inviting two bikers to stay after a 2-minute chat.

The next morning we had breakfast, got packed and said our goodbyes to the guys. It had been an interesting experience and well worth the two day foray. However it was now time to focus and actually get some distance under the tyres. Before leaving Brazzaville we did something quite out of the ordinary and actually checked the calendar. After confirming what month it was we did some calculations and realised we needed to get our backsides into gear if we were going to get through West Africa and make it to Europe with enough to rebuild the bike motors and hit Central Asia, the Stans, Mongolia and Russia at the right time of year.

Qian and Mr Wong bidding us farewell.

Our plan of making swift progress towards Europe had been immediately derailed by the plantation visit. But we would surely not allow ourselves to be sidetracked again we thought………..and then we met Jack. Schedules were abandoned. Adventures ensued.

Earths-Ends

Earths-Ends

Recent Comments